When my ex-wife Lisa called from

L.A. in August of 2002, after being out of touch for several years, to announce

that she was planning a trip to Boston, she asked that I contact our old and

mutual friend Danny Panagakos to inform him about the trip. She was working on

a new video project, a kind of autobiography, and wanted to compare and

contrast then and now versions of important people and

places. She was very fond of Danny. His voice advised her. His image lived in

her heart. To Lisa, Danny was a vampire god of the avant-garde. He referred to

her as “Miss Georgette.” I hesitated.

Lisa would not take “no” for an answer. “I’m not sure Danny wants to hear from

either one of us,” I said.

Lisa was fond of Danny. But was he

also fond of her—or of his parents, or even of his wife, Salma? It was not

clear to me that Danny could be truly fond of anybody. Danny and Lisa had, in

fact, slept together during the hallucinated days that preceded our divorce, a

fact about which Danny wasted no time in informing me. He did not want to place

roadblocks on the freeway of our open communication. Did I care? No. It was an omen

of the end of an anachronistic drama. As such, it was welcome. I was, however,

puzzled by this need for confession on the part of someone so incapable of

guilt.

I had no clue as to his motivations

then, at lease none that was allowed to pass my threshold of awareness. Do I

have one now? I don’t have an explanation but I do have a suspicion, and again,

it has to do with drama. There is little reason to apologize to an entity that

does not exist, but, even in the labyrinth of mirrors, the false self needs a

cast of supporting actors. The job of the supporting actors is to chant that

the narcissist is the Minotaur, the devouring god, the black hole at the center

of the labyrinth, towards which virgins of both sexes must converge.

Transgression and loyalty collaborated to feed the appetite of the growing

supernova.

***

After a number of false starts, I

finally managed to track Danny down at the main branch of the Webster Public

Library, where he had worked his way to the top. Founded by Samuel Slater in

1812 and located on Lake “I’ll Fish on My Side and You Fish on Your Side and

Nobody Fishes in the Middle,” as the translation from the Nipmuc goes, Webster

is an old mill town, once famous for the manufacturing of shoes and textiles,

which had been reimagined as an upscale bedroom community, with a

stage-set-style Main Street, during the high-tech “Massachusetts Miracle” of

the 1980s.

The paint on all of the scenery is

fresh. You will not find any worn spots on the railings. There are ordinances

against pigeons pooping on the statues, and for this reason, they have set up

tiny rest rooms. Even the manikins look like Stepford versions of themselves.

As odd as it might seem, such life-like verisimilitude can be spectral, and

such micromanaged quaintness can be more than a bit disturbing. You would think

that you were living in the 1920s, at the latest, and that Norman Rockwell

might, at any moment, wander into the Owl Smoke Shop for tobacco.

Danny was now Director of Library

Services for the town—an odd position for a flamboyant avant-gardist. I stopped

to wonder at how my friend could pour so much energy into library science,

which he hated, and so little into his artwork, which, supposedly, he loved. This

was also one of the last places in which you would expect to find the Minotaur.

A mastery of the Dewey Decimal System was not a classically recognized

attribute. The library was, however, like the labyrinth, a hermetically-sealed

environment, in which the Minotaur could enforce the centrality of his role. A

high percentage of discordant feedback could be purged. Any leakage of his

occult hungers could be plausibly denied. Few traces would be left. Amid the

coolness of the well-lit shelves, the beast’s rage would be more difficult to

detect than the whisper of air from the AC units.

After a wait of two minutes,

Danny's assistant put me through. “Hi Danny, this is Brian,” I said. “Lisa is

planning a trip to Boston next week, and she asked if I could arrange a time

and place for the three of us to meet. She’s working on a kind of video

autobiography, incorporating some Super 8 footage from 1978, in which we were

all doing our best to act experimental. She was hoping to interview both of us,

to revisit some of our favorite places and to cut back and forth between the

present and the past.”

D: “Tell her that I'm busy.”

B: “Lisa is traveling 3,000 miles,

and it’s been eight years since her last trip. Are you sure that you can't set

aside an hour for lunch?”

D: “Salma and I are building a

house in Belize. I'm really very busy.”

B: “Belize! Why Belize?”

D: “I’m disgusted with America. It

has Americans in it, who disgust me. My grandmother died last year. She left me

all of her money, as well as all of her real estate holdings. Money is not an

issue anymore. I've worked enough. Salma and I are planning to retire next

year, in Belize, where small, brown-skinned peasants will worship the ground we

walk on.

“Are you still living on Hemenway

Street, or have they thrown you out yet?”

B: “I moved when I got married

seven years ago. We own a house.”

D: “A house! My, that really is

impressive. Have you published anywhere, or are you still the ne'er do well

that my father always called you?”

B: “I've written four books since

the last time that I saw you. I've published here and there. What about you,

Danny? Are you doing any writing or art?”

D: “I am, but I don't want to talk

about it. You might steal my ideas again. Did you know that I have a radio

show? They pay me to destroy movies.”

B: “Steal your ideas! You've got to

be kidding. You've never actually shown me any of your work, except for that

black matchbook with your name inside.”

And so the conversation went. There

was no rapport, no play of curiosity, not the slightest trace of affection.

“Lisa is going to be disappointed,” I said. “Perhaps you could give her a

call.”

D: “No. You talk to her. She's your

ex-wife. I have no interest in ancient history.”

Towards the end of our conversation

Danny confided, with considerable self-satisfaction, a bit of information that

I found amazing. He said, “I no longer feel inhibited about being a bitch. I

make sure that people know what I think of them. I don't hide my feelings

anymore.” He presented this as though

such an attitude were the sign of some new maturity, as though rudeness were

not the most ancient of weapons in his arsenal. I could not remember a time

when Danny did not feel free to taunt or mock others without the slightest of

provocations. Friends did not get special privileges. Passersby were not

exempt.

I thought back to a lunch at

Bangkok Cuisine that occurred perhaps 12 years before. Our mutual friend Janet

was visiting from New York, and as we were waiting for our Pad Thai and Green

Duck Curry, Danny decided to entertain us with a series of sarcastic improvisations.

He was quite inventively vicious, brilliant in his pantomime of the diners’

gestures and actions. He did not speak quietly, but projected his lines as to

the top seats in the balcony of a theatre. One especially outrageous comment

took Janet by surprise. She snorted, with explosive force, covering Danny with

a large amount of shrimp and lemongrass soup. The man sitting at the next table

turned to him, and said, “I'm glad that she spit on you! I was about to do it

myself.”

Danny was special. Humans were

stupid. Contempt was the most appropriate response to the opinions and activity

of others. As Adam Smith, in The Wealth

of Nations, wrote, “All for ourselves and

nothing for other people, seems, in every age of the world, to have been the

vile maxim of the masters of mankind.” There were those who saw such

“selfishness” as a bad thing. Danny was not among them.

Illustration: Felix Labisse, Hommage a Gilles de Rais,

1957

Continue reading at: https://www.scene4.com/0723/briangeorge0723.html

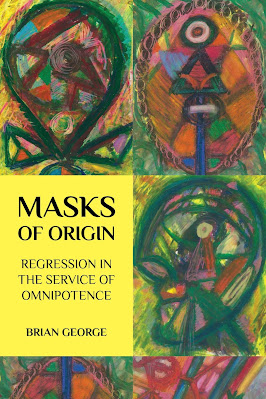

Masks of Origin: Regression in the Service of

Omnipotence, my first book of essays, is available through Untimely books: https://untimelybooks.com/book/masks-of-origin/